The Songwriters Association of Canada (SAC) runs an annual songwriting challenge for its members. I did it last year and found the experience difficult but very rewarding. One of my posts from 2015 is here.

The challenge this year is to write four songs in four weeks under the direction of a set of mentor/challengers. Each week presents a different type of challenge.

SAC members who participate in the challenge are asked to record their result each week and post it online with some commentary.

So here we go …

The Challenge

The challenger is Toronto-based producer and songwriter Murray Daigle, who posted this for us:

Write a song using no more than 2 chords — OR — Write a song that has a single repeating riff (1-bar in length)

This challenge is designed to make writers focus on fundamental “hooks” to create a great song. Also to underline the “catchiness” of the melody, vocal rhythm and lyric will be very important. This limitation takes away the writer’s ability to simply use a chord pattern change and define the musical space. You will actually have to write verses, choruses and bridges that define themselves and “speak” as they should in the context of the song.

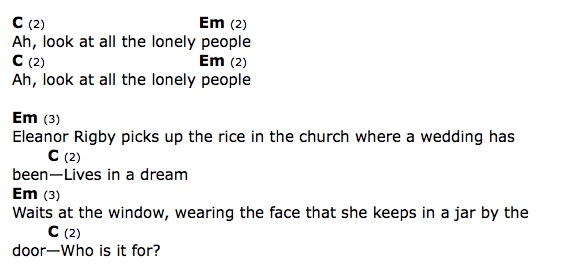

Murray also provided a list of examples for us to consider, including some classics such as “Eleanor Rigby” (Beatles), “Born in the USA” (Springsteen), “When Love Comes to Town” (U2).

The Process

I went with the 2-chord challenge, although I had considered using my looper to try out something with a repeating riff.

Keeping to 2-chords is hard because there is such a strong desire to add a third chord for resolution and/or harmonic progression against the melody. However, the challenge really forced me to pay close attention to melodic and rhythmic elements of the composition.

I listened to some of the examples provided by Murray and adapted a technique from “Eleanor Rigby” that I used to give a sense of movement in the song. Here you can see how the Beatles simply reverse the order of the chords to differentiate between verse and chorus:

Heartwoodguitar.com

I began with several different ideas, playing around with a Travis-picked D/Am progression but dropped it in favour of something a bit more bouncy that moves between the I and the IV (‘C#’ and ‘F#’). This gave me a bit more to play with in terms of the interaction between the melody, lyrics, chord changes.

For the pre-chorus I make a slight change by holding on the IV for an extra bar before returning to the riff. It isn’t quite the same as reversing the order but it does briefly shift the emphasis to the IV and breaks up the pattern.

I also drew on my Pat Pattison theory of songwriting and made subtle changes to the way the lyrics are set between the verses and choruses, “leaning forward” in the chorus to give it a bit more emphasis and remain consonant with the thematic shift in the song.

When I arrived at the end of the second chorus it felt like the song needed a bridge of some kind, so I changed up the rhythm and used a lower and more open voicing of the IV chord:

Capo 1

The lyrics, as often is the case for me, started out largely as muttered gibberish but slowly evolved into a reasonably unified theme. I find the process of just singing nonsense, recording it as a series of takes, and then listening back to it generates lots of interesting and unexpected ideas. Often the gibberish singing produces longer, more rhythmic lyrics than I might otherwise come up with. Revising it all and giving the song a coherent meaning can be difficult but it usually comes together after a couple days.

Lyric worksheet for “Shine On Young Heart”

The Result

Shine On Young Heart

She picks me up in the morning light-

She knows what she’s doing

But for the dust on the heels of my cowboy boots-

I came home with nothing

She dreams of a season scented-

With suntans and Fridays

Sayin’ life is like a long ride in a limousine-

Just lean back and enjoy

She knows just the thing to say-

She puts my mind at ease that way-

It’s a brand new day-

We’ll watch the children play-

You know the sun is here to stay-

Shine on young heart

When I turn back, lose track keeping time-

Choking with fear

She’s there with that halo in her hair-

And whispers for my tears

She knows just the thing to say-

She puts my mind at ease that way-

It’s a brand new day-

We’ll watch the children play-

You know the sun is here to stay-

Shine on young heart

I know you love me

She knows just the thing to say-

She puts my mind at ease that way-

It’s a brand new day-

We’ll watch the children play-

You know the sun is here to stay-

Shine on young heart

(Copyright 2016 Gordon Gow)