“Two Nights in Toledo” is the fourth track on my latest album, Hired Gun. I’ve been delighted to see it getting a bit of play—though I haven’t spotted it turning up in Toledo itself yet. In this post, I want to share a bit about how the song came together, and why it’s a good example of what I enjoy most about songwriting.

So, what comes to mind when you think of Toledo? Toledo, Ohio, that is—not the one in Spain. Before writing this song, I honestly didn’t know much about the city, apart from the fact that in the fall of 2014 I was scheduled for a short work trip to the University of Toledo.

If you’d asked me back then what I knew about the place, my first reference would have been the character Max Klinger (played by Jamie Farr) from the long-running TV series M*A*S*H. Many of you will remember him as the cross-dressing corporal who tried every trick to get out of the army and back home to Toledo. I might also have mentioned the minor-league baseball team, the Mud Hens, mostly because I recall Klinger wearing their jersey in a few episodes. Beyond that, Toledo was a blank space for me.

Leading up to that work trip, I remember coming up with the title “Two nights in Toledo” during a late-night songwriting session. It felt promising, and I started riffing on it. Shortly after came the phrase “could make you a different man.” Now I had a complete line—but no idea where it was heading.

A lot of my songwriting begins this way: something small catches my attention, but without a clear sense of the story behind it. The challenge is to tease out the possibilities—to find a narrative or at least a set of images that might support a lyric. One of the tools I use at this point is the internet. Not as a shortcut, but as a way to gather raw material. Facts, places, details—anything that might help an idea take shape.

So I started reading.

I learned that the Maumee River, which runs through Toledo, had once been a major Indigenous trade route and later became part of the Great Lakes shipping system during the industrial era. Toledo grew into an important port for grain, coal, and iron ore moving through the region. I didn’t know any of this, and I wasn’t sure how it might fit into a song, but the detail stuck with me. Sure enough, the river ended up finding its way into the lyric later on.

Then I found myself reading about the country hit “Lucille”—written by Hal Bynum and recorded by Kenny Rogers in 1977. The opening line—“In a bar in Toledo, across from the depot…”—is the connection. Everyone remembers the hook, “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille,” but that Toledo reference anchors the song in a very particular way. I give a nod to it in my own lyrics—if you listen, you’ll hear it.

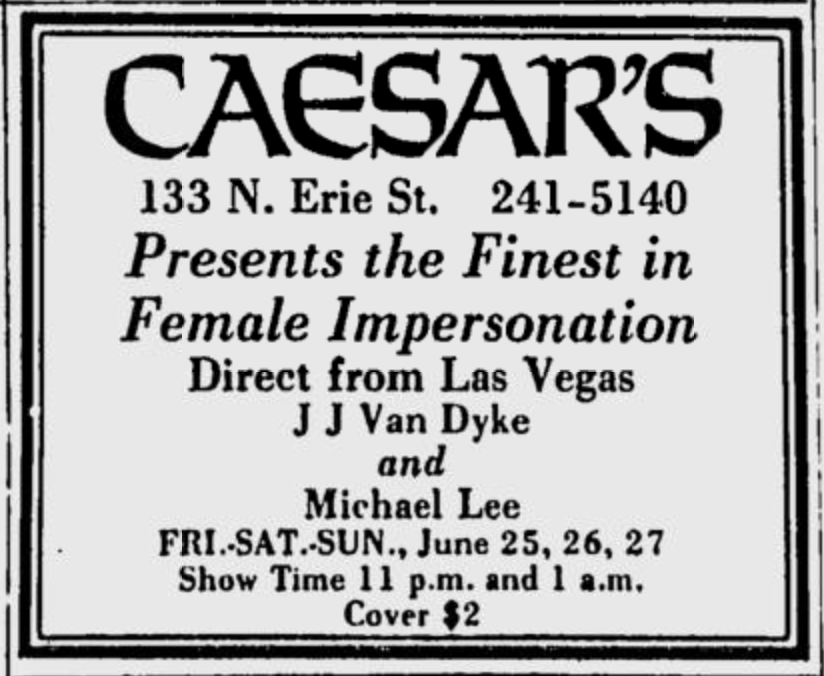

But the real turning point came when I stumbled on a website that mentioned Caesar’s Show Bar. It was a ’70s nightclub run by Joseph C. Wicks, complete with a lighted dance floor, ambitious staging, and a reputation for featuring female impersonators—a distinctive fixture of Toledo’s nightlife at the time.

It’s long gone now, but something about it clicked immediately. Suddenly the line “could make you a different man” had an angle—an unexpected twist, to be sure, but now there was a through-line for the song.

Once that happened, the song pretty much wrote itself. That’s usually how it works for me. You follow the idea wherever it leads. You stay open to surprises. You let your muse be the guide.

The version on Hired Gun is different from the original demo, but I like how it has turned out. It’s got a little of that old school Bryan Adams energy to it, which I don’t mind at all, being a long time fan.

The story behind the writing of “Two Nights in Toledo” is a great illustration of how I work. I might start with almost nothing, a fragment of a lyric usually, but if I stay curious, keep digging, and trust the process, the song usually tells me what it wants to be.